Investigating how the brain encodes sound source elevation

Motivation#

How does our brain know where a sound comes from? 1 An important cue are the time and intensity differences between the ears: if a sound is located to your right, it will be louder at the right ear and arrive there first. These interaural differences inform the brain about the sound’s azimuth but they are not informative about its elevation - for example, a sound in front and straight above you will be the same at both ears.

We can detect a sound’s elevation thanks to the convoluted shape of our ear cups. Because of their asymmetry, the way in which our ears filter incoming sounds changes across space. Our brain can then reverse-engineer the sounds location from the applied filter. 2

But even though sound localization cues have been researched for over a century , it remains unclear how the human cortex represents them - especially what concerns elevation. There is one previous study that found evidence for a cortical representation of sound elevation.

However, that study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) which can accurately localize sources but is temporally imprecise. 3 Also, an fMRI is quite restricting in terms of experimental design because the participant has to lay still is the scanner. For those reasons, we investigated how the brain represents sound elevation using electroencephalography (EEG), which directly measures neural activity with electrodes on the scalp and allows the participant to move around to some extent.

Approach#

One downside of EEG is that it can’t measure specific brain sources but instead picks up a mixture of all signals coming from the brain. What’s more, those signals have to travel through the skull before they reach the electrodes on the scalp which further damps and smears them. This means the effect of interest may be very small.

To overcome this problem we used an adapter-probe design which leverages the fact that neurons decrease their response to sustained stimulation. The probe (white noise played trough open headphones) preceded every stimulus (burst of noise from one of four loudspeakers). Probe and stimulus were cross-faded so that sound intensity remained constant during the transition 4.

Exposition to the probe attenuates sound-responsive neurons, so that the response to the stimulus is dominated by neurons that are sensitive to the change in elevation. Occasionally, after hearing the stimulus, the participant was asked to indicate 5 where the sound came from which ensured they paid attention.

Key Results#

We found that neural responses decreased in amplitude with increasing elevation. This was the first time someone demonstrated cortical encoding of sound elevation with EEG, and the result was similar to the aforementioned fMRI study. This is compelling because the fact that the neural processes of sound localization can be measured in the same way with fMRI and EEG constrains possible origins 6.

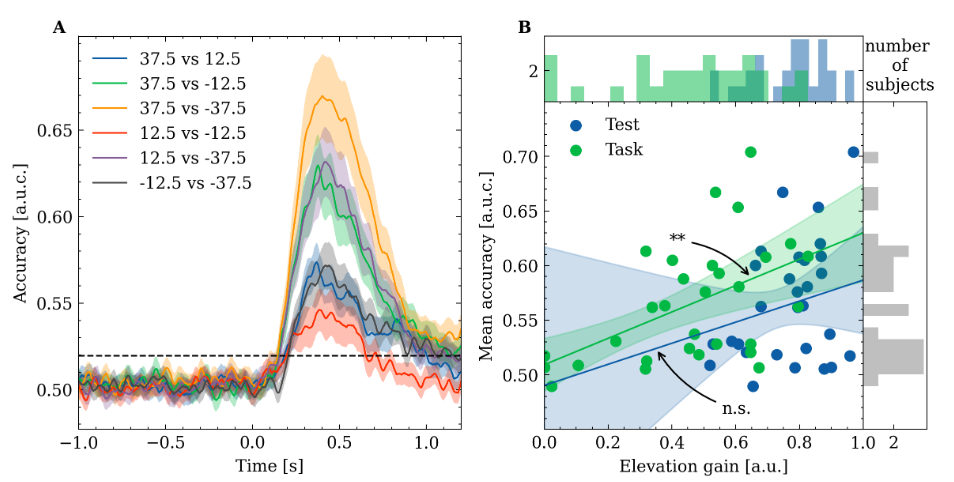

To quantify how distinctly different sound sources are represented we decoded elevation from the brain responses using multivariate logistic regression. We found that elevation could be decoded for a sustained duration after hearing the stimulus and that decoding accuracy was greater the further the sound sources were apart (panel A in the plot below). Across participants, the overall decoding accuracy was predictive of how well they did in the localization task. This suggests that the representations we found are not just related to acoustic correlates but really underlie the perception of sound elevation.

Resources#

If you are interested in reading about this project in detail you can find it as a preprint on bioArXiv. The manuscript is currently under review at an academic journal. All data and code are publicly available. They can be obtained using the software datalad:

datalad install https://github.com/OleBialas/elevation-encoding.git

cd elevation-encoding

datalad get *

This will download all of the code and data (~19GB)

Footnotes#

I wrote a blog post on this question (in German): “Wo die Musik spielt: Wie wir wissen, woher ein Geräusch kommt” ↩︎

So darwin was wrong when he stated that “The whole external shell of the ear may be considered a rudiment, together with the various folds and prominences” (The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 1871) ↩︎

That is because fMRI does not measure neural activity directly but instead measures local changes in blood oxygenation due to the metabolic demand of active neurons. ↩︎

The loudspeaker arrangement is explained in more detail in the post on our experimental setup ↩︎

We instructed the participants to turn their head to the direction of the perceived sound and used a deep neural network to estimate their head pose - this procedure is described in another post ↩︎

Often fMRI and EEG don’t co-vary like this. For example, the neural firing rate could decrease (lower fMRI signal) but at the same time they could synchronize more (higher EEG signal). ↩︎